| |

Chapter 16

King Loc did not laugh long; on the contrary, he hid the face of a very

unhappy little man under his bedclothes.

Thinking of George of the White Moor, prisoner of the Sylphs, he could

not sleep the whole night. So, at that hour of the morning when the dwarfs

who have a dairymaid for a friend go to milk the cows in her place while

she sleeps like a log in her white bed, little King Loc revisited Nur

in his deep well.

“Nur," he said to him, “you did not tell me what he was

doing among the Sylphs."

The old Nur thought that King Loc had gone out of his mind, and he was

not very frightened, because he was certain that King Loc, if he became

mad, would certainly turn into a graceful, witty amiable, and kindly madman.

The madness of the dwarfs is gentle like their sanity and delightfully

fantastic. But King Loc was not mad; at least he was not more so than

lovers usually are.

“I mean George of the White Moor," he said to the old man,

who had forgotten this young man as completely as possible.

Then the learned Nur arranged the lenses and the mirrors in a careful

pattern, but so intricate that it had the appearance of disorder, and

showed to King Loc in the mirror the very shape of George of the White

Moor, such as he was when the Sylphs carried him off. By properly choosing,

and skilfully directing the instruments, the dwarf showed the lovelorn

king the whole adventure of the son of that countess who was warned of

her end by a white rose. And here expressed in words is what the two little

men saw in the reality of form and colour.

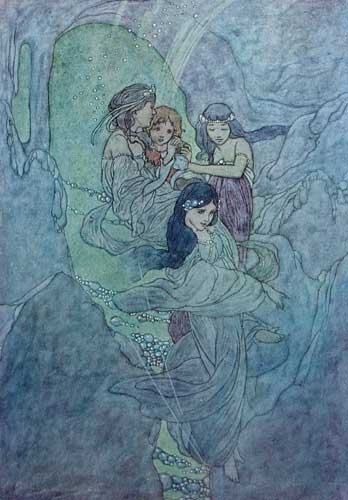

When George was carried away in the icy arms of the daughters of the

lake, he felt the water press his eyes and his breast, and he thought

it was death. Yet he heard songs that were like caresses, and he was steeped

in a delicious coolness. When he opened his eyes again he found himself

in a grotto; it had crystal pillars in which the delicate tints of the

rainbow shone. At the end of this grotto there was a large shell of mother-of-pearl,

irisated with the softest colours: it was a canopy spreading over the

throne of coral and weeds where sat the queen of the Sylphs. But the aspect

of the sovereign of the waters had lights softer than the sheen of mother-of-pearl

and of crystal. She smiled at the child brought to her by her women and

let her green eyes rest on him long.

“Friend,” she at length said to him, “welcome in our

world, where you will be spared every pain. For you, no dry books or rough

exercises, nothing coarse that recalls the earth and it’s labours,

but only the songs, the dances, and the friendship of the sylphs.”

So the blue haired women taught the child music, waltzing, and a thousand

amusements. They loved to bind on his forehead the shells that starred

their own locks. But he, thinking of his country, gnawed his fists in

impatience.

The years went by, and George’s wish to see the earth again was

unchanged and fervent, the hardy earth burnt by the sun, frozen by the

snow, the native earth of sufferings and affections, the earth where he

had seen, where he wished to see Bee again. Now he was growing into a

big boy, and a slight golden down ran along his upper lip. Boldness came

to him with his beard, and one day he appeared before the queen of the

Sylphs, and having bowed, said to her:

“My lady, I have come, if you deign to permit it, to take leave

of you. I am going back to the Clarides.”

“Dear friend,” the queen answered, smiling, “I cannot

grant you the leave you demand, for I keep you in my crystal manor to

make you my friend.”

“My lady,” George replied, “I feel unworthy of so great

an honour.”

“This is the effect of your courtesy. No good knight ever thinks

he has done enough to win the love of his lady. Further, you are yet too

young to know all your merits. Be sure, dear friend, that nobody wishes

you anything but good. You only have to obey your lady.”

“My lady, I love Bee of Clarides, and I will love no other lady

but her.”

The queen, very pale, but still more beautiful, cried:

“A mortal woman, a gross daughter of men, this Bee, how can you

love that?”

“I do not know, but I know that I love her.”

“Very well, you will recover.”

And she detained the young man in the delights of the crystal manor.

He did not know what a woman was, and was more like Achilles among the

daughters of Lycomedes than Tannhauser in the magic mountain. So he wandered

gloomily along the walls of the immense palace, looking for an opening

to run away; but on all sides he saw the floods enclosing his luminous

prison in their mute and magnificent kingdom. Through the transparent

walls he watched the anemones bloom and the coral flowering, while purple,

azure, and golden fish sparkled and sported above the delicate madrepores

and the glistening shells. These marvels did not interest him; but lulled

by the delicious songs of the sylphs, he slowly felt his will give way,

and his whole soul dissolve. He was all slackness and indifference, when

he found by chance in a gallery of the palace an old worn book of vellum,

studded with copper nails. The book, found in a wreck at the bottom of

the sea, dealt with chivalry and ladies, and there were told at length

stories of the adventures of heroes who went through the world fighting

against giants, redressing wrongs, protecting widows, and assisting orphans

for the love of justice and the honour of beauty.

George flushed and grew pale in turn with admiration, shame, and anger

at the tale of these splendid adventures. He could not contain himself:

“I also,” he cried, “will be a good knight! I also will

go through the world punishing the wicked and helping the unhappy for

the good of men and the name of my lady Bee.”

Then his heart grew great with courage. He strode with drawn sword through

the crystal mansions. The white women fled and vanished before him like

silvery waves of a lake. Their queen alone saw him come upon her unmoved.

She fixed on him the cold look of her green eyes.

He rushes to her; he cries;

“Unclasp the charm which you have thrown on me. Open the road to

earth. I wish to fight in the sun like a knight. I wish to return to love,

to suffer, and to struggle. Give me back the true life and the true light.

Give me action and achievement; if you do not I will kill you, wicked

woman!”

She shook her head smiling, to say “no.” She was beautiful

and calm. George struck her with all his strength. But his sword broke

against the glittering bosom of the queen of the Sylphs.

“Child!” She said.

And she had him shut up in a kind of crystal funnel which formed a cell

under the manor; round it sharks prowled, opening their monstrous jaws

armed with a triple row of sharks teeth. And it seemed as if at each charge

they must break the thin partition of glass; it was not possible to sleep

in this strange cell.

The point of this submarine funnel rested on a rocky bottom which was

the dome of the furthest and the least known cavern of the Empire of the

dwarfs.

This is what the two little men saw in the course of an hour as exactly

as if they had followed George all the days of his life. The ancient Nur,

after having displayed the cell scene in all it’s sadness, spoke

to King Loc much in the way a showman when he has shown the magic lantern

to the little children.

“King Loc,” he said to him, “I have shown you all you

wished to see, and, your knowledge being perfect, I can add nothing to

it. I am not anxious to know whether what you have seen has pleased you;

it is enough that it is true. Science takes no account of pleasing or

displeasing. It is inhuman. It is not science, it is poetry which charms

and consoles. That is why poetry is more necessary than science. King

Loc, go and compose a song.”

King Loc went out of the well without speaking a word.

Previous Chapter Next

Chapter

|